Calgary Through the Eyes of Writers

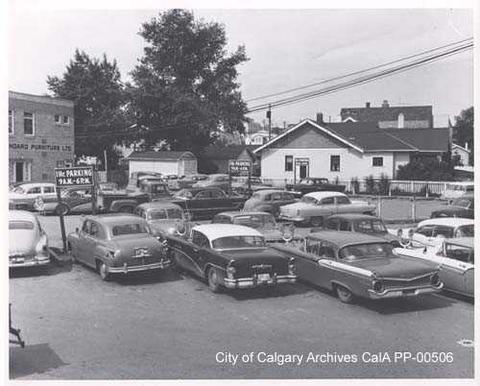

Pearl Miller ran her brothel in this house at 526 - 9th Avenue SE in the late 1920s. Today, Loft 112 remembers Miller with its Pearl's Place Creative Residency, a program that operates in the Loft's literary/creative space located directly behind what used to be Pearl Miller's house. (Photo: Calgary Public Library)

“I don’t suppose it’s a surprise,” poet Nancy Jo Cullen writes in her preamble to Pearl, “that the details of a whore’s life have been lost to history but I find her story emblematic of the renegade individualism Alberta claims to love.” Calgary-born Cullen imagines the life and times of Pearl Miller, a legendary brothel owner, madam and early Calgary entrepreneur. Miller arrived in the city in 1914 and embarked on a 28-year career operating a string of city bordellos, including one near Calgary’s posh Mount Royal neighbourhood. Around 1926, Miller purchased a wood-frame house on 9th Avenue East. In 1942, after three months in jail, Miller’s career shifted: she spent the remainder of her days saving women from a life of prostitution. Miller died in 1957 and her storied house was demolished sometime after 1971.

Oh fairest house to shelter easy girls,

That thereby carnal lust shall never die,

And thy parlour shall host the tender churl,

Who leaving wife at home with whore doth lie.

Six hundred square feet and no mortgage due,

Although the city starves, thy walls shall flourish.

Harlots give proof of what man will pursue

Though work be lost and children be malnourished.

An excerpt from Nancy Jo Cullen's “526 – 9 Avenue SE,” Pearl (Calgary: Frontenac House, 2006)