I first met Susan Calder in the early 2000s at Calgary’s Alexandra Writers’ Centre Society, back when AWCS called the basement of Inglewood’s Alexandra School home. Soon, Susan and I formed a writing group with Calgary poet Marilyn Letts. We read early chapters of Susan’s first novel A Deadly Fall and celebrated its publication in 2011. Years before I started exploring Calgary on the literary page, reading Susan’s Calgary novel set in the Ramsay neighbourhood and roaming around other parts of the contemporary city was a rare treat.

A Deadly Fall was the first of Susan’s quartet of Paula Savard mysteries – each one set in and around Calgary. You can find the series at BWL Publishing.

In December, Susan published her 6th novel A Killer Whisky – a mystery set in 1918 Calgary, a young city changed by war and coping with a deadly pandemic. It’s full of twists and turns and surprising events.

I invited Susan to chat with me about her first foray into historical fiction. Here’s our conversation.

Susan, congratulations on your new book! How did you come to write a novel set in 1918 Calgary? What in particular caught your imagination about the city during that era?

Thank you, Shaun, for your good wishes and for inviting me to your blog.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in March 2020, I became intrigued with the 1918 influenza pandemic and read several books about the Spanish flu, as it was called then. The fears, restrictions, and medical advice had much in common with our pandemic situation. Then I started a new novel, Spring Into Danger, set in Calgary during COVID-19, and got the idea of inserting chapters with a parallel storyline set during that earlier pandemic. The idea didn’t work out, and I cut those chapters from the book. But I’d discovered that fall 1918 was an interesting time in Calgary—the flu and Prohibition shut the city down, World War One was drawing to a close after four long years, and people were preparing to enter a changed world. This inspired me to turn my abandoned chapters into a short story that morphed into a novel.

Staff at Calgary’s Bank of Commerce during the 1918 influenza epidemic. Susan’s novel also features these gauze masks people wore in the day. (Photo: University of Calgary Archives & Special Collections)

What kind of research did you do to get a feel for 1918 Calgary?

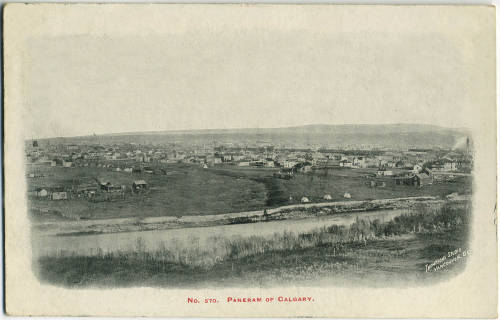

I read many books. The two most useful types were books about Calgary history written by Max Foran and other local historians, and fiction written by Southern Alberta authors of the early 20th century. Shaun, you recommended and loaned me a number of novels that gave me a sense of the city, streets, homes, and Calgary daily life circa 1918. As a bonus, the novels were delightful to read. The non-fiction history books included photographs of buildings, streets, vehicles, and people of the times. Also helpful were old maps, old newspapers, Google searches, and historical fiction. In addition, Shaun, you and I did field trips to a couple of neighbourhoods featured in A Killer Whisky. Some buildings constructed before 1918 are still standing and I used them as locations in the novel.

I’m glad you enjoyed those early Calgary novels. Remind me which ones you read? Did anything in particular surprise you in those stories?

The Shadow Riders and The Magpie’s Nest by Isabel Paterson, The Cow Puncher by Robert J. C. Stead, and Cattle by Winnifred Eaton Reeve aka Onoto Watanna. I was surprised by the strength of the female protagonists in these novels. They were more spirited and independent than I’d viewed our great-grandmothers of that era. These early 20th-century story characters wouldn’t be far out of place in today’s society.

This 1923 novel by Calgary-based writer Winnifred Eaton Reeve touches down in the city during the influenza epidemic. A centenary edition of the novel is available from Invisible Publishing.

Your novel is filled with spirited and independent women. One of them, Katharine, lives in Tuxedo, and much of the novel’s action unfolds in and around her home. Why did you choose this neighbourhood for A Killer Whisky?

I wanted Katharine to live close to the city limits to show Calgary as a growing place that drew people from other parts of Canada and the world. From an old streetcar map, I discovered that in 1918 Tuxedo was at the northern end of the streetcar line. I later learned the neighbourhood was developed during Calgary’s Pre-World War One building boom by speculators who’d bought up much of the land north of the Bow River. They thought nothing of greasing the palms of civic leaders to get the streetcar line through their properties to increase the land value. I liked that rough aspect of Calgary history for the story backdrop.

Calgary poet Elaine Catley moved to Tuxedo in 1921, shortly after the influenza epidemic. In this photo, you can see the edge of the prairie behind Catley’s home at 311 - 28th Ave NE. (Photo: Catley family)

You also take us into the Hicks Block, an Edwardian commercial building that still stands at 1804 1st Street NW – and your police detective lives in Mewata, a neighbourhood we now call Downtown West. Did your story touch down at any other historic Calgary landmarks?

A couple of scenes take place at the Calgary General Hospital, then a four-storey brick and sandstone building that opened in Bridgeland in 1910. Between 1949-1953 a larger structure was built on the same site at Centre Street northeast. In a controversial move, the province of Alberta demolished the historic hospital in 1998. I vividly recall watching the implosion on TV and hearing the boom all the way to my home in the south part of Calgary. The novel also makes several references to the Palliser Hotel, which opened in June 1914 and still stands as a city landmark.

The Hicks Block at 1904 1st Street NW features in Susan Calder’s A Killer Whisky. (Photo: City of Calgary Inventory of Evaluated Historic Resources)

After A Killer Whisky, do you foresee writing any more Calgary historical mysteries? If so, is any particular period or place calling your name?

I’m mulling an idea for a historical novel inspired by my grandparents’ experience as Czech immigrants to Canada. I see the first quarter of the novel being set in Europe and the remaining three quarters set in Canada. My characters will land in Montreal, where I spent the first part of my life, but they might go to Calgary right away or later in the story. Originally, I’d thought of setting the novel during World War Two but now I lean toward the World War One era mainly to make use of the research I’ve done for A Killer Whisky. Rather than a whodunit mystery, this new novel would be mystery/suspense dealing with a crime that forces the protagonist to leave her homeland. So, I don’t know if I’ll write another Calgary historical mystery, but if I do, it will probably be set during or shortly after World War I. As for places, my characters might wind up in Calgary’s Bridgeland neighbourhood, where many immigrants from Central Europe settled in the early 20th century.

One last question for you, Susan. A Killer Whisky is part of BWL Publishing’s Canadian Historic Mysteries series. Can you tell us a little more about the series and the places and time periods some of your fellow writers are visiting?

This is a series of twelve historical mystery novels written by different authors and set in Canada’s ten provinces and two of our territories. A Killer Whisky is the Alberta story. We authors were free to write whatever we wished as long as the novel was a mystery and set in a real historical period. Some of the novels explore true events—the trial of a Black slave accused of setting a devasting fire in Montreal in 1734 and the mysteries surrounding the drowning of artist Tom Thomson in 1917. Others weave a fictional story through a time and place like the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush. The series is a great way to get a cross-country sense of Canadian history while reading entertaining stories.

Indeed! Sounds like a wonderful tour of the country and its history. Thanks for chatting with me, Susan!

It was a pleasure, Shaun.

Susan will be launching A Killer Whisky in Calgary in late March. For details, check her website -- susancalder.com.