Calgary through the eyes of writers

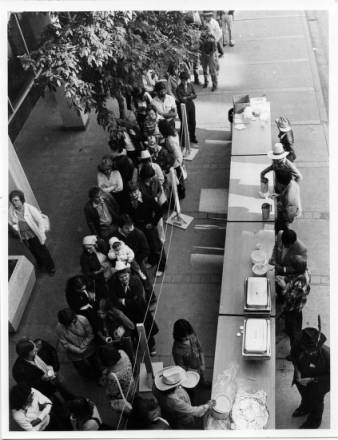

Stampede breakfast downtown Calgary, circa 1970-90. (Photo: Calgary Public Library)

“Stampede coming,” Aritha van Herk writes, “always in the seventh month, the off-centre pivot of the year.” van Herk immerses herself in the city’s signature event. Observer and participant, she writes a poetic primer on the Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth. Infield and midway, princesses and parade, chuckwagons and hangovers. Through her poet’s eyes, Stampede is a prism through which to consider the city, and the westness of west. But first, breakfast. Pancakes served up on a street corner. A kind of Calgary communion.

The breakfast shuffle. A queue of weary clerks and landsmen waiting for

their servings of pancakes and bacon, some fat to fight the nausea, some

carbs to play it forward. A conga file, a column of supplicants salivating for

the hew of dough, the sweet melt of syrup and butter under the tyranny of

a plastic fork and knife, an inadequate napkin, the buckling paper plate.

One sausage for reward.

Aritha van Herk, Stampede and the Westness of West (Frontenac House, 2016)