Calgary through the eyes of writers

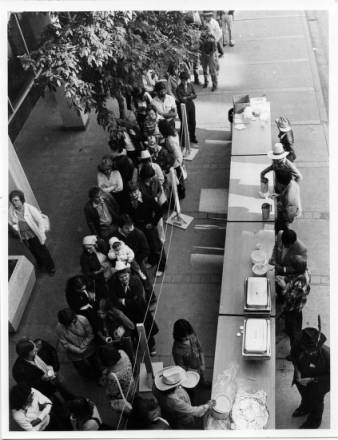

Calgary Stampede midway circa 1959 (Photo: Calgary Public Library)

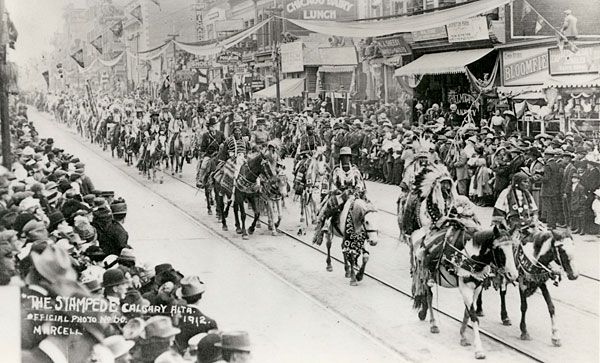

Thirteen going on fourteen, Wendy Kettle visits the Stampede grounds with her parents and big brother Jamie. She’d rather be watching the disco dancer’s show. Her girlfriends are right: the dancer is the best thing at the Stampede this year, leaping and sliding in his tight white pants and silky white shirt to the soundtrack of Saturday Night Fever. At the noon show, he smiled at her. At the afternoon show, he gyrates, as if for her. In his final side-split, he points his index fingers at Wendy – “like guns, bangbang”– and she returns the gesture. When the show ends, the dancer slips away and Wendy heads to the corn dog tent where her family is waiting.

Wendy’s family spent a long time discussing which part of the grounds they should all visit next. Wendy thought the discussion was a waste of time since they always did the same thing every year anyway. Wendy’s dad liked to walk through the Stampede barns and look in every stall, and comment on the livestock as though he was raised on a Cochrane ranch rather than in the city. Wendy’s mother liked to tour the Big Four building to look at kitchen gadgetry like Popeil’s Kitchen Magician and the Showtime Rotisserie. After oohing and aahing at every single vendor, she’d whisper to Wendy, “I need that appliance like I need a hole in the head.” And Jamie would choose something, usually the Funhouse or a ride that the Kettles could handle, but enough out of their usual box so that they would have a hilarious time and talk about it for weeks.

It was all so predictable and unfair. The dancer took only a few minutes. Everything else took forever.

Barb Howard, “Saturday Afternoon at the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, 1977” (Lofton8th, 2016)