Calgary through the eyes of writers

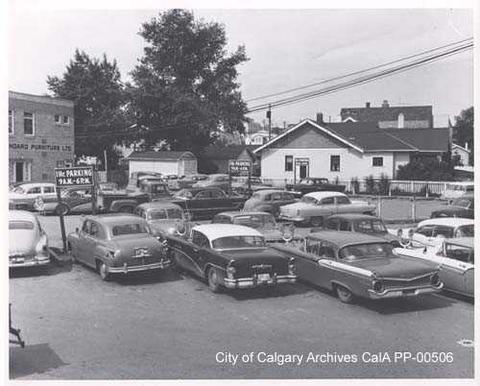

The "Crestview" neighbourhood in Mark Giles' story resembles Calgary's Fairview: a community developed in the late 1950s in keeping with the principles of the "Neighbourhood Unit Concept." According to the then-city planning director, Fairview's various features would make it a "thoroughly desirable place to live." (Image & quotation from Robert Stamp's Suburban Modern: Postwar Dreams in Calgary, 2004)

Colm and his young family have settled down in a bungalow in the SE Calgary suburbs. But his post-war neighbourhood-in-transition near Heritage Drive is anything but peaceful: Colm and his next door neighbour are at war. There's the Harley Davidson fired up on Sundays and left to rumble in the yard. The steady stream of visitors – pizza and dial-a-bottle delivery guys, bikers, college students, business men, matrons – people dropping things off, and picking things up. And a yappy Yorkshire terrier that never shuts up. In the din of his neighbour’s life, Colm concocts a plan.

He will build a fence. The highest fence allowed by law. A thick, high, soundproof impenetrable fence. A fence without chinks or cracks between boards. He will allow no knotholes through which to peer, no handholds or footholds on which to hoist oneself. A fence sunk into the ground under which no small dog, no rodent, no child can burrow. A Berlin Wall, a Great Wall of China, a Hadrian’s Wall, a Maginot Line. When he finishes the fence, he will plant a high hedge, a hedge that will grow skyward past the fence, past the height of the house itself. A thick, high hedge.

He has downloaded the development permit application and all the necessary supporting documents from the city website (the same website where he accessed the Animal Control Bylaw). He spends every tidbit of spare time planning and designing the fence. He uses his laptop and the CADD tools from his work. He knows how much concrete he will need for the foundation and the pillars, how many pallets of cinder blocks, how much sand, how many cubic feet of earth he will need to displace. He knows how much it will cost. He develops a budget and construction schedule. He refines the design, consults his engineering references, revised and revised again. The fence will be a marvel. The fence will be a neighbourhood landmark. He will name it.

W. Mark Giles, “Knucklehead,” Knucklehead & Other Stories (Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2003)