Calgary through the eyes of writers

"Waiting for the Parade" by Calgary artist Stan Phelps (Photo: Arcadja Auctions)

In the summer of 1993, Paris-based, Calgary-born novelist Nancy Huston returns to her hometown. She's been away for 25 years, and is about to see her first Alberta novel, Plainsong, published. On Stampede parade day, she and her young family head downtown. After the first band marches past, Huston bursts into tears. As a girl, she dreamed of being in such a marching band, wearing a short pleated skirt and twirling a baton. In an instant, she pulls herself together. “Roland Barthes, I tell myself (using French theory to protect myself from Albertan emotion), could have written a ‘mythology’ about this strange event.”

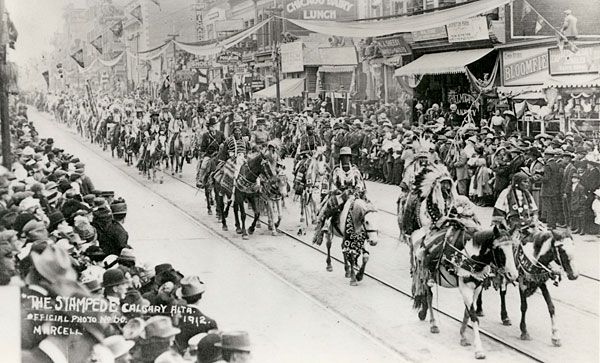

What unfolds before our eyes for a full three hours, in the freezing rain, is a succession of bands and floats celebrating every ethnic group in this province’s population: Indians of all tribes, proudly decked out in their traditional costumes (“You see, Daddy?” says Sasha. “You told me Indians didn’t wear feathers any more, but you were wrong!”), Ukrainians, Irish, Hungarians, Dutch, Scots, Germans – and the one and only message conveyed to the enthusiastic audience is: “We are here.” On the spectators’ side, the one and only response to this message is the cry of “yahoo!” endlessly reiterated… “Yahoo!” As far as I can tell, this word is my city’s one distinctive contribution to the history of humanity.

Nancy Huston, “A Bucking Nightmare,” Saturday Night (June 1997)