Calgary Through the Eyes of Writers

Calgary school buses at rest. (Photo: Calgary Sun)

Craig Davidson’s year of a driving a special needs school bus in Calgary is almost over. He has come to love the six children on his route at the southern edge of the city. “A bus full of nerds,” he calls them: people as quirky as he is. Driving a school bus has changed him. When he started the job, he was facing failure as an aspiring writer and despair. Now he finds himself at the centre of a small, astonishing community. On his last week on the job, he wakes to the spring cawing of magpies. He drives up MacLeod Trail to the impound lot to pick up his bus, and, settled behind the wheel, joins the convoy of school buses, “a stately yellow flotilla, dispersing into the urban grid.” At his first stop, he picks up Jake, a wheel-chair-bound kid with cerebral palsy: a storyteller like Davidson, and a kindred spirit. As Davidson continues along his familiar route of “sleepy thorough-fares and cul-de-sacs,” he reflects on the kids on his Calgary school bus and his remarkable year.

They rode because their parents told them to and they obeyed. But, I thought: the odd moment may persist.

Maybe it would be that afternoon in January when I had to get the bus inspected, which made me late. Darkness was falling by the time everyone was on board. A flash squall touched down. Snow curled over the Rockies on a bone-searching wind that screamed through seams in the airframe, rocking the bus on its axles. We charted a path on roads frozen to black glass. Snowflakes glittered in the headlights like a million airborne razor blades. I’d merged with a rural highway on the city’s southernmost scrim. The glow of car headlights pooled up and across the night rises. The moisture of six bodies fogged the windshield; I’d rolled down the window and wind howled with such force that the tears forced out of my eyes were vaporized before they touched my ears. The tires lost traction on a strip of black ice and hit the rumble strips before returning to the tarmac. My fists were gripped fierce to the wheel – which was when Jake began to sing.

It’s cold outside, there’s no kind of atmosphere

I’m all alone, more or less…

Darkness wrapped tight to the bus, snow pelted the windows, and Jake belted out the theme song to Red Dwarf in a high clear British-accented contralto.

…Let me fly, far away from here

Fun, fun, fun, in the sun, sun, sun…

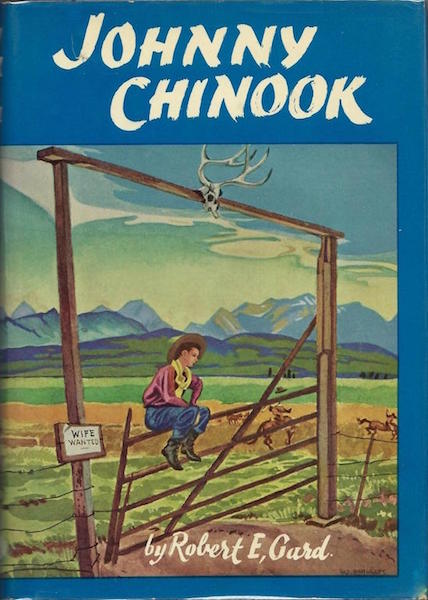

Craig Davidson, Precious Cargo: My Years Driving the Kids on School Bus 3077 (Toronto: Alfred A Knopf, 2016)