Calgary Through the Eyes of Writers

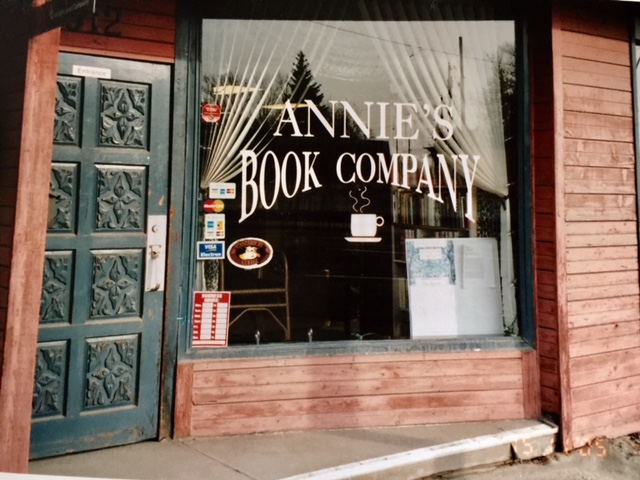

Annie Vigna (aka Wesko) ran her bookstore on 16th Avenue North between 1996 and 2007. The widening of the avenue in 2005 contributed to her decision to wrap up the business. Annie's Books lives on in the hand-crafted lectern at the Alexandra Writers' Centre. (Photo: Annie Wesko)

Sixteenth Avenue North: a 26.5-kilometre stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway, an urban artery, and in the 1990s, on a few blocks near 10th Street West, a neighbourhood of bookstores. Bob Baxter was first on the block, opening his used bookshop in 1960. In 1996, Annie Vigna, with a degree in Russian literature in hand and a sense of entrepreneurial adventure, bought the shop and made it her own – a place for bookhounds, Red Hatters and writers. On a spring weekend, poet Bob Stallworthy takes us inside a literary reading at Annie’s Book Company where art mingles with the avenue.

in a bookshop on sixteenth avenue

we spend the first nice Spring Sunday

poets tell us about somebody else’s life

hell there is life here too

the shelves in this store are stacked

floor to ceiling with it

we take it all very seriously

words in shouts squeals whispers

from the mouths of readers

backdropped by the street

that screams in blue and red flashing lights

going east

rumbles in eighteen forward gears

heading west

while quietly shelved second-hand words

and windows focus sunlight

from out there

on our word dust

hanging in the air in here

Bob Stallworthy, Optics (Frontenac House, 2004)