Calgary Through the Eyes of Writers

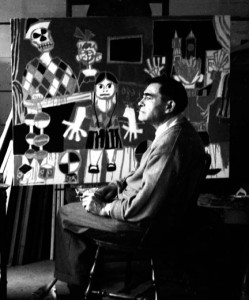

Maxwell Bates in his studio (Photo: University of Victoria)

Maxwell Bates, one of Canada’s preeminent modernist painters, was also a poet. Born in Calgary in 1906, he grew up in a cultivated English home across from the Lougheed mansion on Thirteenth Avenue West. Like his paintings, Bates’s poetry shows a preoccupation with human presence in the landscape. In an early poem, the fifteen-year-old Bates listens to Calgary through his bedroom window. “The city murmurs” not only with the sound of bird song and barking dog, but with the “faint sound of hammer.” In a poem written his early twenties, Bates explores the city’s industrial landscape of “moulder and decay”: workers’ shacks and brick kilns, railway tracks and smoke stacks that “smudged the sky.” In a later poem, he considers “the great, human stain of the city.” He see himself as separate, but connected: “I belong to those streets.” In “Intimations,” a poem written in mid-life, he finds not only inspiration but transcendence in the city where he grew up and later returned to live.

Upon the houses

Black and beautiful,

Light of the moon

Shadowed dim silver;

And in my soul,

Feelings of some scarcely perceptible

Great beauty,

Some words of God,

Not quite invisible.

Maxwell Bates, “Intimations,” Far-Away Flags (1964)