Calgary through the eyes of writers

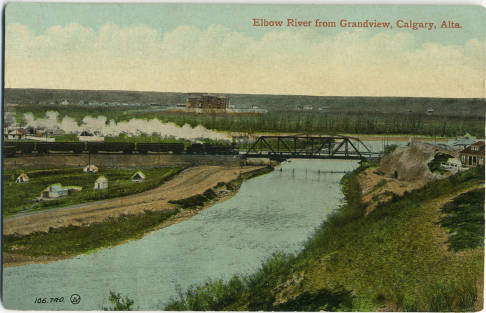

A steam engine crossing the Elbow River seen from a bluff in what we now call Ramsay, an area once known as Grandview. (Photo: Calgary Public Library Postcards from the Past)

Annie Clemens is adrift. It has been two years since her lover, Sylvie was killed in a car accident and Annie is struggling to move on. She meets Martha Rigg, a widowed activist who is protesting the Mulroney government’s free trade campaign. She spray paints her message around town on the “things nobody really owns, hoardings and underpasses. Secret places.” Annie does not have strong feelings about free trade, but in Martha she sees a kindred spirit coping with grief. She decides to ride shotgun on one of Martha’s late-night painting sprees. From the Fort Calgary parking lot, the two women walk along the bike path toward the railway tracks in Ramsay. They carry a can of red spray paint and a stencil with a silhouette of Canada. SOLD, it reads. REALTOR OF THE YEAR: BRIAN MULRONEY. FREE TRADE ISN’T.

We arrived at the Elbow River, so still, as if it had come to a halt and were contemplating changing direction. The underpass was not far off. Lights had been installed and were permanently on; too many homeless in this part of the city, a dark dry place would be dangerously inviting. Best to illuminate. As we drew closer, in fact, the brilliance of the lights was repellent. I wondered if we might not be thrown backwards by the strength of the wattage or destroyed the way insects can be by light. But no, we entered the little tunnel unchallenged.

“This looks like a good spot,” said Martha. “Let’s cover this up, whatever this is. Let’s see, ‘Metallica fucking, fucking rules,’” she read. “I think a nice map of Canada would be more suited to this space.”

Martha fished out the stencil and held it against the concrete, then handed me the paint. I sprayed with abandon. Red streaks, immediately began to drip from the forty-ninth parallel. Overhead, on the tracks, voices could be heard. “Wake up, everybody,” one of them said. “Do you hear me?” he shouted. “Wake up ya bunch of fuckers.”

“Can you shut him up?” a female voice asked.

“Shut up, Mike,” said a third voice, male, tired.

“Wake up” was heard again, only quietly this time, conversationally, followed by the splattering of a stream of piss into the Elbow River.

Marion Douglas, Bending at the Bow (Press Gang, 1995)