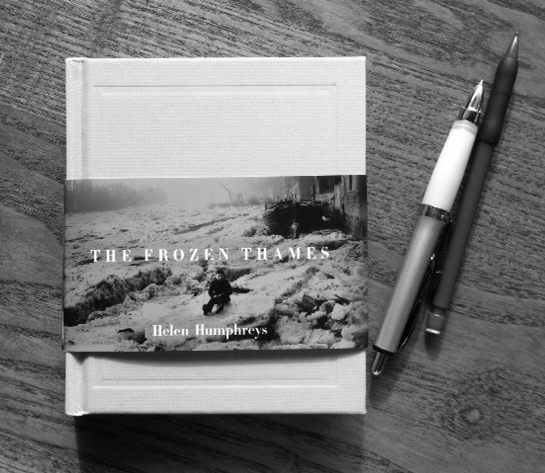

I found this small book – not much bigger than a thick stack of postcards – in Vancouver last month, at a small, quirky shop called The Paper Hound. Helen Humphreys’ The Frozen Thames was on a shelf marked “Books with Maps.”

There is only one map in this beautiful volume: a section of one of the earliest printed maps of London, circa 1574. In it, the river is unfrozen and muddy, the quilt-squares of land, spring green – the same way the landscape looked when my husband and I hiked sections of the Thames Path Walk a year ago last May.

We followed a guide printed from the website before we left. Fumbling with the truncated instructions (I hadn’t accounted for the different paper size in the UK), we relied on small blue path markers and my husband's nose for direction.

I didn’t need a map to follow Humphreys’ story, or rather, stories – forty of them, one for each of the forty times the Thames River has frozen solid. Taken together, they are what Humphreys calls “a long meditation on the nature of ice.”

As I read, I scribbled notes, not about Humphreys’ riveting text, but about an idea that’s been turning in my head for the past several weeks. My story idea has nothing to do with rivers or ice, but as I read Humphreys' prose, the quality of her attention sharpened and suffused my own. I slowed down, considered the narrative choices she made, the material she eased from history, artefact and imagination, the connections she forged. Her techniques offer a guide of sorts, a way into envisioning my story. Her prose sets my own idea in motion.

In the postscript, Humphreys leaves us with snippets of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando – a novel that begins on the frozen Thames. “This is a story,” Humphreys writes, “that thaws the imagination, sets it spinning along a swift current of words.”

As is The Frozen Thames. A book chock full of maps after all.