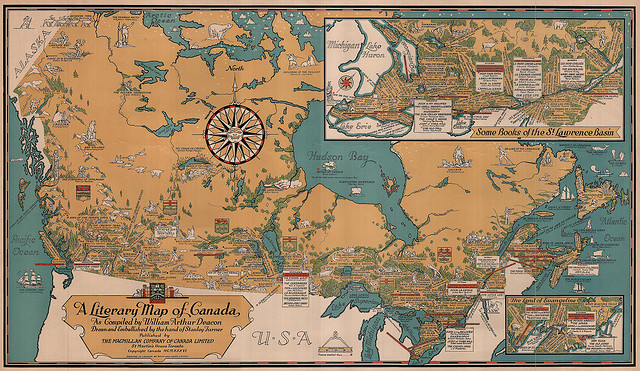

Calgary through the eyes of writers

The Bow River near Calgary's Inglewood, January 1, 2016 (Photo: Shaun Hunter)

Leona is home after spending the Christmas holidays with her parents in BC’s Lower Mainland. Usually, she’s anxious to get back to her job as a senior editor at one of Calgary’s newspapers. This year, she is reluctant to resume her daily life. The holidays were happily uneventful: no sign of the panic attacks that plagued her in the fall. From the warmth of her apartment, she pauses to consider the Calgary weather. She has no choice but to go out into it: her friend Marion is moving into an old house across the Bow River, and Leona has offered to help.

The day in January that Marion moved was very cold but clear, except that ice fog breathed from the earth, obscuring the outlines of things, filling the air with white; the sun, struggling to penetrate it, had lost much of its light and all of its warmth by the time it got down to ground level. Leona, gazing from her apartment window, thought it looked like another planet out there. The coldness was a thing of unquestionable malevolence. It would strike skin numb, and make breathing painful. She thought there was a lot to be said for the colorless rain which had fallen on southwestern British Columbia at Christmas.

L. R. Wright, Among Friends (Doubleday, 1984)